The Battle of Agincourt 25 October 1415

The Hundred Years’ War was a 116-year conflict (1337-1453) between England and France that started as a dispute over claims to the French throne. Made up of a series of military campaigns punctuated by multiple truces, it evolved into a broader conflict that saw the introduction of new innovations and tactics. Chivalry saw both its heyday during the war as well as the start of its decline. What we know today as nationalism also had its birth.

The Battle of Agincourt took place on 25 October 1415 and proved to be the most important as well as influential battle of the war, with far-reaching consequences, some of which still exist today. The background events leading up to the unplanned battle are important to consider as they greatly influenced its outcome.

In 1413, Henry V ascended to the English throne. His holdings in France had been reduced to a pathetic pittance of its former glory: only the port city of Calais along with a small piece of Gascony remained. Henry decided to change that. Several compelling factors invited this decision. French pirates were running wild in the English Channel, the English barons and even Parliament were eager for military action, and the French king, Charles VI, had gone insane. [1] Believing he was made of glass, Charles forbade his courtiers from coming near him and had special clothing reinforced with metal rods made to keep him from shattering should he fall or bump into anything. [2] This debilitation left him incapable of effectively ruling his kingdom, so his nobles split into factions that quarreled among themselves. This chaos invited invasion and Henry was willing to take advantage of it.

He raised an army of 10,000-12,000 and sailed for Normandy. He first laid siege to the city of Harfleur. However, the siege took far longer than anticipated, nearly 6 weeks, and proved extremely costly in manpower losses. Casualties, desertions and a terrible wave of dysentery had reduced the army to 6000: 1000 knights and men-at-arms as well as 5000 longbowmen. [3] Knowing his force was in serious trouble, Henry decided to make for Calais. French defenses prevented a timely crossing of the Somme River, forcing Henry to find a ford further upstream. This allowed the French enough time to assemble a large army under Constable Charles d’Albret and Marshal Jean II le Meingre (called Boucicaut) to intercept him.

By the time the French caught up with the English, Henry’s army was in real trouble. It had just marched 200 miles (320 kilometers), was still dealing with dysentery and was starving as the French had used a scorched-earth policy leaving the English with little food and few supplies. [4] The armies came within sight of each other near the village of Agincourt on 24 October. They set up camp for the night to prepare for the big battle the next day. Then it began to rain.

There is some dispute about the size of the French army. Estimates range from 20,000-36,000 [5], 20,000-30,000 [6], to 18,000. [7] In any case, the English were hugely outnumbered, especially in cavalry. The battle should have been a literal piece of cake for the French who even referred to the upcoming clash as a ‘joust,’ [8] but several mitigating factors gave the English some hope.

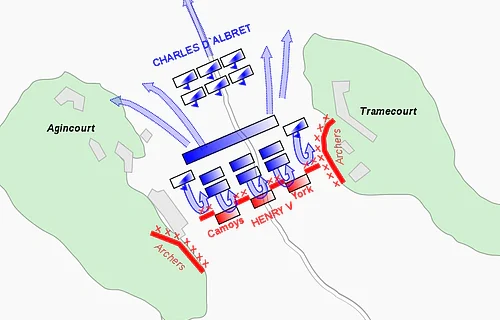

The first was the battlefield itself. Look at the map to see how much it favored the English. The French had the advantage in overall numbers and knights. On an open battlefield, the French would have been able to outmaneuver, outflank and ride over the English. However, the map clearly shows that forest anchored both English flanks funneling the French army into a tight space, forcing them to attack frontally. This partially nullified the French numerical advantage. Then there were the ground conditions. The open field between the 2 patches of forest was agricultural land that had just been plowed, making it soft and bad for cavalry charges. An all-night rain worsened the situation by turning the field into a massive sea of mud. The final negative factor for the French was their lack of a unified command. Lacking an effective king to lead them like Henry led the English forces, the French nobles were an unruly group that did not want to take orders from each other. The recipe for disaster was complete.

When the 25th dawned, Henry appraised the situation and made some significant moves. He split his archers into 2 equal groups, stationing them on the flanks of his army so they could fire on the advancing French from the sides, better enabling them to injure or kill their horses. In addition to that, he instructed the archers to place two rows of sharpened stakes 6-feet (1.8 meters) long in front of their positions angled to impale any charging horses. [9] Only 300 yards (270 meters) separated the two armies.

At first, the 2 sides just stared at each other. Henry needed the French to attack because his forces were too small to go on the offensive, plus he wanted to take advantage of the mud. The French were unsure of what to do. They realized the mud would seriously affect their mobility and some sane voices called for waiting until the ground dried before attacking. [10] Many other nobles were inpatient to attack so they could destroy the dreaded English and capture prisoners for ransom. For a while, reason held out.

Henry needed to provoke the French into a premature attack, and he figured out a way to do it. Even though the enemy was too far away to take much damage from his archers, he ordered them to open up a barrage anyway. The problem for the French was that the longbow was the machine gun of the Middle Ages. Skilled archers could fire 15 arrows per minute [11] and they could pierce plate armor at close range. In the first 30 seconds of the barrage, 25,000 arrows descended on the French army. [12] Even though they caused few serious casualties, the blow to French pride proved insurmountable.

The French had crossbowmen and some archers of their own. They should have been ordered to advance and then fire on the longbowmen to try to neutralize them, but units of French knights impatiently pushed them out of the way or just rode over them in their desire to strike back at the English. Immediately, the mud became a critical problem as the horses sank in it deeply enough to prevent them from gaining enough speed for a proper cavalry charge. Their slow speed allowed the longbowmen to fire more and more arrows at them at closer and closer ranges.

It took only a minute-and-a-half for the initial units of French knights to reach the English lines, but in that short time, the longbowmen fired at least 75,000 arrows at them. [13] Many horses went mad with pain as the English arrows hit them from the flanks. Throwing their riders, they tried to escape the battlefield but the crush of so many men and animals forced into a small area, coupled with the second line of troops moving up from behind, created total chaos that resulted in many Frenchmen getting trampled by their own steeds. Those knights who made it to the longbowmen were confronted by the double-row of sharpened stakes that prevented the horses from advancing any further. At such close range, no armor on Earth could protect man or beast from the English arrows.

The lines of French infantry following behind the knights became disrupted almost immediately. Between the churned-up mud, arrow storms and trying to dodge fleeing horses, they also had to climb over the bodies of their fallen compatriots. Anyone who fell had a very difficult time getting up again even if unwounded because their armor was so heavy and they kept floundering in the viscous mud. Having wounded or dead people fall on them or new lines of warriors climbing over them didn’t help. Many actually suffocated in the confusion.

However, once the hand-to-hand fighting started, the English line wavered and almost broke. The Duke of York and Henry’s brother, the Duke of Gloucester, were killed. Henry himself received such a heavy blow to the head that his helmet was dented. [14] The situation looked very dark for the English when the longbowmen came to the rescue. Unlike French archers, once close combat began, their English cousins dropped their bows, drew their knives, axes and mallets, and entered the fray. Any French knights who fell or became isolated from their comrades became easy prey. All the armor in the world won’t protect a fighter from a knife through his visor or being hamstrung from behind. The French began to retreat but those trying to fall back bumped into the fresh troops trying to move forward. The crush became so bad that individual fights couldn’t swing their weapons! [15] Facing such disaster, first individuals, then entire sub-units began surrendering.

It seemed like the English had victory in the bag. Suddenly, 2 alarming developments threw everything into doubt. First, Henry’s baggage train in the rear area carrying his treasure and supplies was attacked. Thinking it was more serious than just a bunch of looters (which it was), Henry sent significant forces to deal with the situation. Then his left flank came under severe pressure as an invigorated French attack started making headway, threatening to collapse that part of the line. [16] Henry called for reserves, but there were none available. The only uncommitted forces he had left were the knights guarding their French prizes. He desperately needed them to re-enter the battle, but they refused as their prisoners represented great wealth and honor. Then Henry gave the most controversial order of his life: ‘Let everyone of my lances kill his French prisoner.’ [17]

That was an illegal order by both the rules of chivalry and the accepted rules of war. His knights refused to carry it out. Henry next instructed 200 of his archers to march the prisoners away and execute them, which they did. Between 2000 and 3000 Frenchmen were killed by this action. [18] Only the most valuable were spared.

The attacking French units witnessed the illegal bloodshed, striking a serious blow to their morale. Freed from the burden of their former prisoners, the English knights rejoined Henry and strengthen the weakening left flank. The French attack wavered, then broke leading to a retreat. Mounted units escaped the carnage but men on foot as well as those lying prostrate were killed in their thousands.

“King Henry V, with victory at hand, raised his banner. A cheer went down the line. The king knelt to give thanks to the Lord. He then sent for Montjoie, the French herald whose duty it was to observe the fight and act as an impartial umpire…

‘Sire, you have sent for me.’

‘Herald, how call you the battle?’

‘Une victoire anglaise – an English victory.’

‘Tell me, herald, what is the same of yonder castle?’

‘Agincourt, sire.’

‘Then let it be known that stout and brave Englishmen achieved victory at the Battle of Agincourt.’” [19]

There is a dispute over the casualties each side suffered. For the English, between 400 and 1000 perished; for the French, between 6000 and 13,000 met their end. However, the numbers don’t give justice to the true scale of the catastrophe the French had suffered. A large percentage of the French nobility had been killed, ‘including 3 dukes, six counts, 90 barons, the Constable of France, the Admiral of France and almost 2,000 knights. This culling of the French nobility meant there was limited resistance to Henry’s next moves in terms of large field armies clashing.’ [20]

The French went on to refer to the battle as ‘the accursed day.’ [21] They also developed a hatred for anything English, a feeling that would carry on for centuries. [22] ‘Even in today’s colloquial French, everything evil is anglaise.’ [23] Another consequence of the war was the beginning of nationalism. The English and French began thinking of themselves as English and French, not just the subjects of King Such-and-Such. They also started to view themselves as one nation fighting another nation, not just one king fighting another, a view that we still have with us in the world today.

Henry capitalized on his great victory by later capturing Normandy and marching on Paris. Henry was so successful that the 1420 Treaty of Troyes made him the regent of and heir to Charles VI. He even married Charles’ daughter, Catherine of Valois, who then became the Queen of England, giving birth to Henry VI. However, all those great victories and grand plans came crashing down when Henry died in 1422. Joan of Arc appeared on the battlefield 7 years later. English fortunes would then go into terminal decline, giving ultimate victory in The Hundred Years’ War to the French.

Sources

Battle of Agincourt | Facts, Summary, & Significance | Britannica

Battle of Agincourt – World History Encyclopedia

Corrigan, Gordon. A Great and Glorious Adventure: A Military History of The Hundred Years’ War. London, UK: Atlantic Books, 2014.

Durschmied, Erik. The Hinge Factor: How Chance and Stupidity Have Changed History. London, UK: Hodder and Stoughton, 1999.

The French King Who Believed He Was Made of Glass – JSTOR Daily

- World[↩]

- Jstor[↩]

- Britannica[↩]

- Britannica/World[↩]

- World[↩]

- Britannica[↩]

- Hinge p.28[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Gordon p.242/World[↩]

- Hinge p.34[↩]

- World[↩]

- Gordon p.246[↩]

- Ibid., p.247[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- History/Britannica[↩]

- Hinge pp.42-43[↩]

- Ibid., p.43[↩]

- Ibid., pp.43-44[↩]

- Ibid., pp.44, 45[↩]

- World[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Hinge p.46[↩]

- Ibid. p.46[↩]